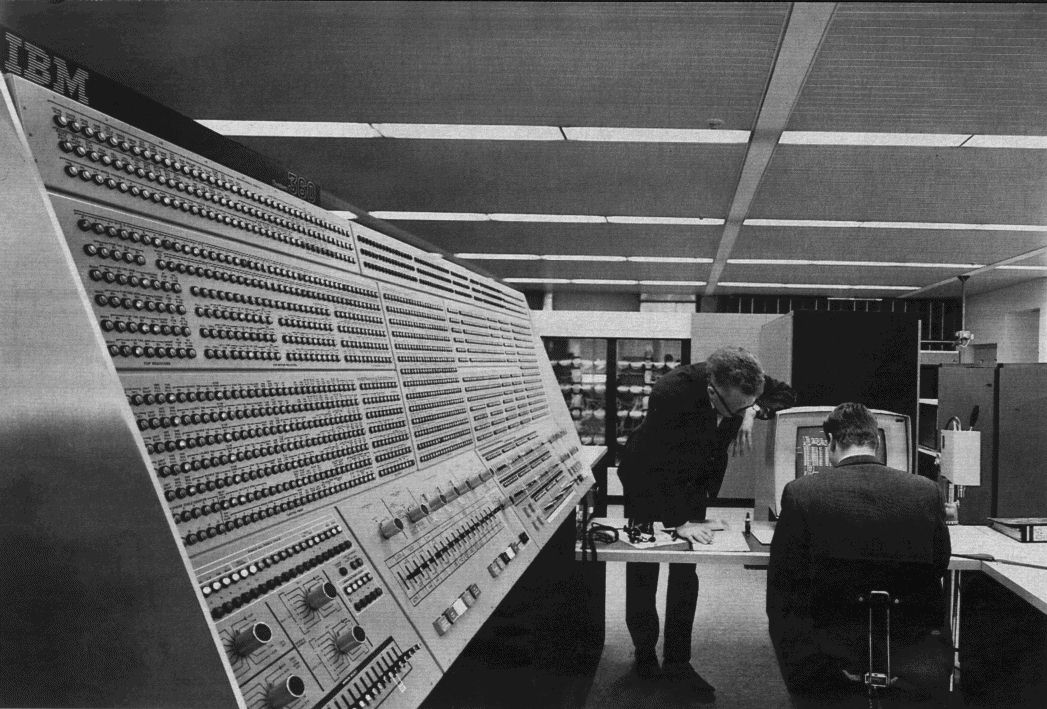

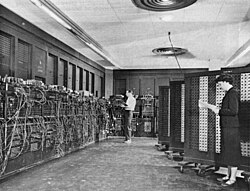

A great war was brewing in the soul of the machine. In one camp were the logicians of Symbolic AI, who saw intelligence as a set of rules to be programmed. In the other were the connectionists, led by Geoffrey Hinton, who believed intelligence had to be grown, learned from the bottom up like a brain. But this profound debate was happening inside a locked room, a fortress guarded by a priesthood of experts. For all its world-changing potential, the computer in the early 1960s was an oracle, a terrifyingly complex beast that spoke only in arcane languages of punch cards and magnetic tape. To speak to it, you had to be an initiate.

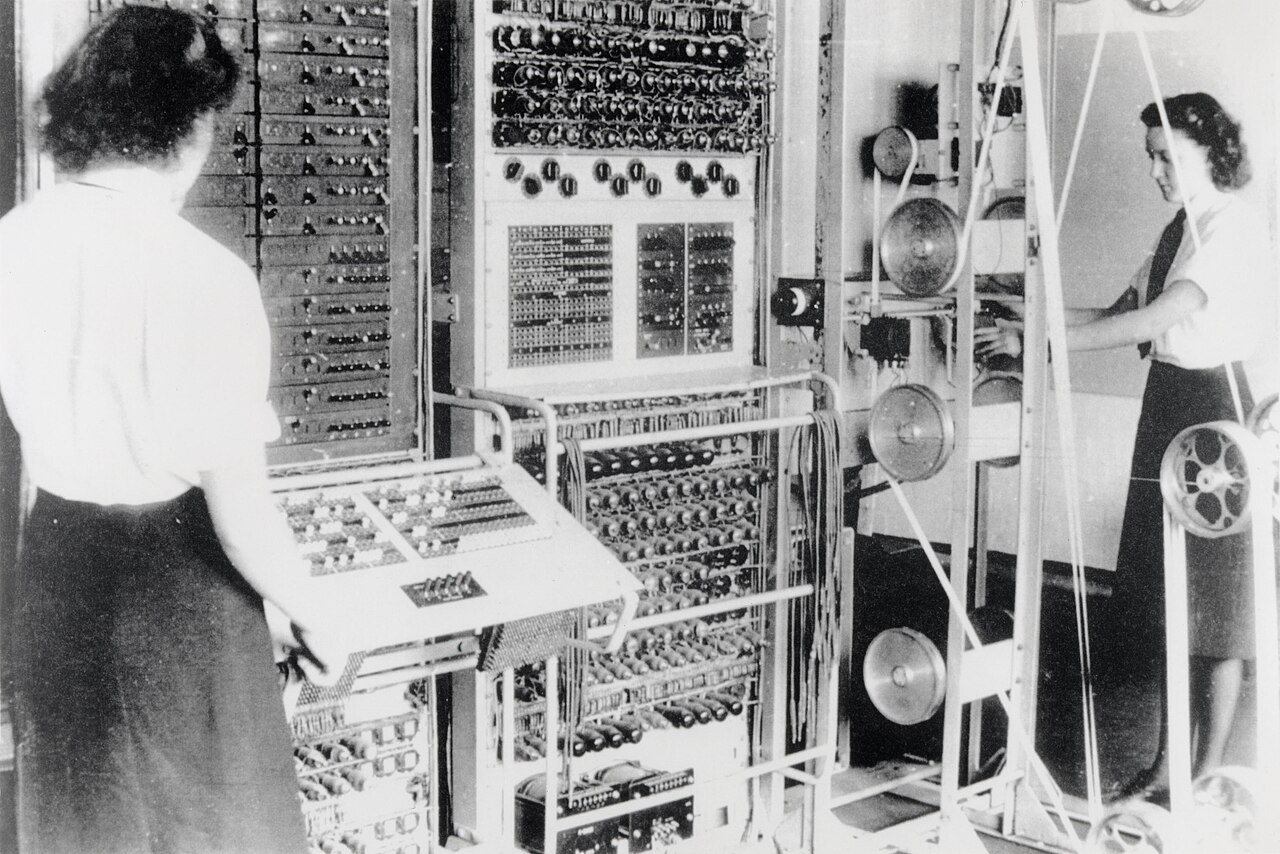

This was the fundamental barrier. The power of computation was real, but it was inaccessible. The process of programming was a slow, punishing ritual. An engineer would write a program, painstakingly transcribing it onto a deck of paper punch cards. That deck would be handed to an operator, who would feed it to the giant mainframe computer. Hours, or even days, later, the programmer would get back a printout—often just to discover a single typo had ruined the entire run.¹ It was a system designed for experts, a system that actively resisted experimentation and play.

To break this barrier, the story returns, once again, to the quiet campus of Dartmouth College. Two mathematicians there, John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz, saw a different future. They weren't trying to build an artificial mind; they were trying to educate human ones. They had a radical vision: that computing should not be a specialized, technical discipline, but a core part of a liberal arts education, a tool that should be as accessible to a history major as it was to a physicist. They wanted to make the computer a pencil, not a cyclotron.²

To do this, they first had to demolish the one-at-a-time, batch-processing model. Their solution was the Dartmouth Time-Sharing System (DTSS), a revolutionary system that allowed dozens of users to connect to a central computer simultaneously through simple teletype terminals. It created the illusion that every single user had the entire machine to themselves. This was the birth of interactive computing. For the first time, a user could have a "conversation" with the machine, typing a command and getting a response in seconds, not days.

But this breakthrough created a new problem. The programming languages of the day, like FORTRAN and ALGOL, were still too complex for beginners. They needed a language as simple and conversational as their new system. So, they invented one.

They called it BASIC: the Beginner's All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code.³ It was a language built for clarity, not for computational efficiency. It used simple, English-like commands: PRINT, INPUT, IF...THEN. It had line numbers, so a student could easily fix a mistake without retyping everything. At 4 a.m. on May 1, 1964, Kemeny and Kurtz ran the first BASIC program on their time-sharing system. In that quiet pre-dawn moment, the world shifted.

The creation of BASIC was an act of profound democratization. It was the moment the keys to the kingdom were handed from the priesthood to the people. Within a few years, BASIC would spread from Dartmouth to become the default language of the coming personal computer revolution. A generation of future programmers, from Bill Gates to Steve Wozniak, would get their start typing 10 PRINT "HELLO WORLD" into a terminal. The power to command a machine was no longer a dark art. It was a skill that could be learned by a teenager in their basement.

The individual was now empowered. A single person could sit at a terminal and talk to a single machine. But these conversations were still happening in isolation. The machines, and their newly empowered users, were still islands. The next great leap would not be about empowering the individual, but about connecting them. The next revolution would be to take these isolated islands of intelligence and weave them together into a vast, interconnected web.

Citations:

¹ Kurtz, Thomas E. "BASIC." Published in History of Programming Languages, edited by Richard L. Wexelblat, Academic Press, 1981, pp. 515-537. A firsthand account by one of the creators. The book is a standard reference, available at university libraries and for purchase.

² Kemeny, John G. Man and the Computer. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1972. In this book, Kemeny lays out his vision for the future of computing and its role in education and society. Available at libraries and used booksellers.

³ Dartmouth College. "The Birth of BASIC." An online exhibition detailing the history of the language and the time-sharing system, with access to original documents and photos. Available to explore at the official Dartmouth website.

.png)

.jpg)

_School_-_Charles_Babbage_(1792%E2%80%931871)_-_814168_-_National_Trust.jpg)