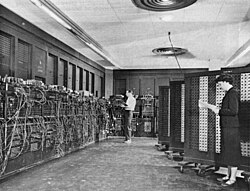

The invention of the transistor had solved the problem of the body. The unwieldy, unreliable glass cages of the vacuum tube era were giving way to solid, silent, and efficient silicon. The path was now clear for computers to become exponentially smaller, faster, and more powerful. But this very success made the original, haunting question—the one that had echoed from Ada Lovelace's study to Alan Turing's lonely meditations—more urgent than ever. What was this new power for? Was it just for calculating artillery tables faster, or could it be used to replicate the very process of human thought?

In the summer of 1956, a handful of the brightest minds wrestling with this question were drawn to the sleepy campus of Dartmouth College for what they called the "Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence." Its leader was a young, brilliant, and fiercely optimistic mathematician named John McCarthy. He, along with Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and the father of information theory himself, Claude Shannon, had put together the project's proposal. Its core premise was one of the most audacious and consequential conjectures in modern history.

"The study is to proceed," they wrote, "on the basis of the conjecture that every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it."¹

Think about the sheer ambition of that sentence. Not just calculation, not just logic, but every aspect of intelligence. Creativity. Language. Common sense. They were proposing that the very essence of human thought was a puzzle that could be solved, a process that could be codified and, ultimately, replicated in a machine. To give their quest a focus, and to distinguish it from the more limited fields of cybernetics or automata theory, McCarthy coined a new name for the field. He called it Artificial Intelligence.²

The Dartmouth workshop was less a series of breakthroughs and more a declaration of independence. It was the moment that AI was formally born, establishing itself as a distinct scientific discipline. For the next two decades, the field would be dominated by the intellectual framework that solidified that summer: the idea of "Symbolic AI."

The central belief of the symbolic school was that thinking was, at its core, a form of information processing. The human mind, in this view, was a system that operated on symbols—words, ideas, concepts—by manipulating them according to a set of logical rules, much like a player in a game of chess. Intelligence wasn't some mysterious, ethereal property; it was a kind of computation. The path to creating AI, therefore, was to discover those rules and program them into a machine.

And for a time, this approach was stunningly successful. Just months after the workshop, Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon demonstrated a program called the Logic Theorist. It was a program that, by manipulating logical axioms, was able to independently prove 38 of the first 52 theorems in Whitehead and Russell's monumental Principia Mathematica. In one case, it even found a proof that was more elegant than the one the original authors had discovered.³ This was not just calculation; it was a machine that could reason.

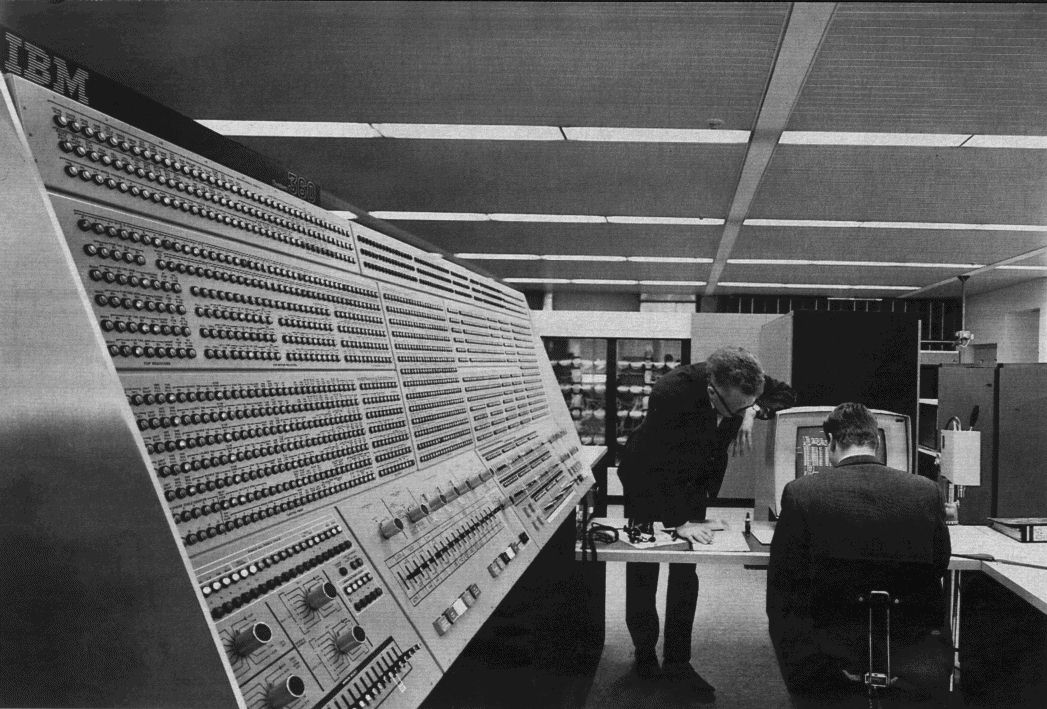

The dream now had a name and a clear path forward. The quest to build a mind had begun. But this grand ambition was running headfirst into a messy, practical problem. The AI pioneers were writing their brilliant programs, but the computers they had to run them on were a chaotic zoo of incompatible machines. Each one was a unique, handcrafted island, speaking its own private language. To build the future of intelligence, you first needed a stable ground to build it on. The industry was in desperate need of a common language, a universal standard that could finally tame the hardware chaos.

Citations:

¹ McCarthy, J., Minsky, M. L., Rochester, N., Shannon, C.E. "A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence." 1955. This is the founding document of the field of AI. A digitized version of the full proposal is available to read online.

² Nilsson, Nils J. The Quest for Artificial Intelligence. Cambridge University Press, 2009. A comprehensive academic history of the field, with detailed accounts of the Dartmouth workshop. Available for purchase or at university libraries.

³ Russell, Stuart J., and Peter Norvig. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. 4th ed., Pearson, 2020. The standard textbook in the field, it provides a detailed explanation of the Logic Theorist and its significance. Available at major booksellers.

.png)

.jpg)

_School_-_Charles_Babbage_(1792%E2%80%931871)_-_814168_-_National_Trust.jpg)